Central question: Is Batman’s no‑kill rule actually protecting Gotham?

I finally decided to work through my backlog and loaded up Batman: Arkham City. A close friend, a lifelong Batman fan, told me this was the best of the trilogy. Better than Asylum. Better than Knight. The definitive Batman experience.

Something felt wrong almost immediately.

The fight with Penguin ended and a thought hit me harder than any punch combo. Why didn’t I just kill him? The answer came fast. Batman doesn’t kill.

That rule used to feel noble to me. Playing the game made it feel hollow.

Moments later, Bruce Wayne casually changes into his Batman gear on a rooftop. In public. Nobody notices. That broke immersion in a small way, but it planted a bigger seed. I was going through motions without feeling invested.

Then came Catwoman. Save her. Again.

I stopped playing.

Why save her when I know how this goes? She escapes. Joker escapes. Gotham pays the price. I realized I did not feel like my time mattered because the outcome was already written.

So I asked the real question. Why was Batman pissing me off?

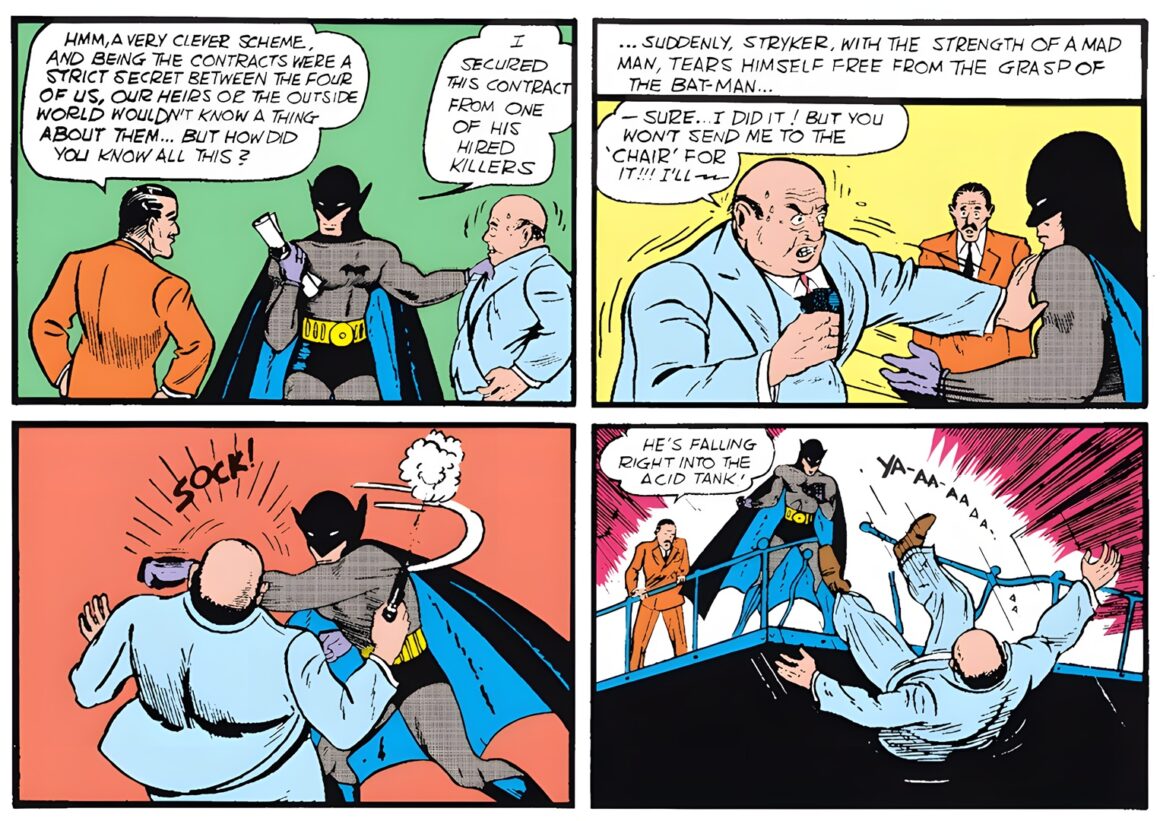

Batman originally killed, and that changes everything

Digging into Batman’s history made the frustration click.

Batman did kill.

In his earliest appearances in Detective Comics #27 in 1939 and the stories that followed through early 1940, Batman was a ruthless vigilante. He used guns. He caused deaths directly. He was written as a dark detective who ended threats permanently.

That version of Batman lasted a short time, but it existed. Roughly a year. The shift away from lethal force was not driven by story logic. It was driven by business.

DC wanted Batman to appeal to children. Comics began drifting toward a younger audience because of their visual style and mass distribution. Editorial mandates followed. No guns. No killing. Robin was introduced. Batman became a role model.

Once I understood that, Batman’s strict moral code stopped feeling like a hard‑won ethical stance. It started feeling like a corporate artifact that later writers were forced to justify.

That matters for the lore.

When corporate decisions become moral absolutes

Batman’s no‑kill rule is often treated as sacred. Break it, and Batman “goes bad.” That framing works emotionally. It struggles logically.

Let’s take the Joker.

Batman refuses to kill him. Fine. That is Batman’s boundary.

Why does everyone else have to share it?

If Superman, using his own moral judgment, decides that Joker poses an ongoing existential threat to innocent life, Batman stopping him becomes something else entirely. It becomes Batman prioritizing his psychological need for moral purity over the lives Joker will inevitably take.

Thousands die because Joker keeps escaping. Entire sections of Gotham are destroyed. Trillions in damage accumulate across stories. The justice system fails repeatedly.

At some point, refusing to act stops looking like restraint and starts looking like negligence.

Batman’s fear is treated as everyone’s responsibility

A common defense is that Batman fears what he would become if he killed someone. That fear is valid. Trauma shapes people.

What does not make sense is allowing that fear to dictate outcomes for an entire city.

Batman is human. He has gadgets, training, and money. Superman is a being with godlike abilities. The idea that Superman cannot permanently stop Batman if he went dark does not hold up under scrutiny.

Yet Batman’s rule somehow overrides everyone.

The city cannot execute Joker.

Heroes cannot intervene decisively.

The cycle continues.

At that point, Batman’s role shifts from protector to gatekeeper.

The narcissism framework explains the pattern

This is where my personal lens matters.

My father was diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder. Because of that, certain behavioral patterns stand out to me faster than they might for others. That awareness does not automatically make every observation correct. It does mean I pay attention to patterns of control and self‑justification.

Viewed through that lens, Batman’s behavior raises uncomfortable questions.

- Grandiosity shows up in the belief that only he can save Gotham, and only on his terms.

- Control appears when he forces allies and institutions to operate within his moral framework.

- Empathy becomes selective. He speaks about protecting innocents while allowing innocent people to die. He knows they will die.

- Manipulation emerges when personal boundaries are framed as universal moral law.

- Consequences fall on everyone else. The city burns. Civilians die. Batman retains his self‑image.

- Accountability never arrives. He operates outside the law while preventing others from acting decisively within it.

Alfred once warned Bruce that he and the Joker were opposite sides of the same coin. That line lands harder the older I get.

Does someone who lets innocents die still qualify as good?

This is the point where many readers push back.

Batman saves people. All the time.

He also allows mass death to remain inevitable.

A moral framework that protects the self while sacrificing the future does not feel heroic to me. It feels compromised. From that perspective, Batman stops looking like a flawed hero. Allowing innocents to die is evil.

Why I could not finish Arkham City

I struggle to play “bad” characters in games. I always have. In my head, killing villains to stop future harm places my characters in a grey space. They are acting to reduce suffering, not feed ego.

Playing Arkham City forced me into Batman’s moral rigidity. I could not resolve the dissonance. So I stopped.

Instead, I watched a full playthrough online.

I loved it.

Removing myself from control made the story easier to appreciate. Ironically, it pulled me back into comics as a reader rather than a participant.

Funny how that works.

Batman’s no‑kill rule began as a business decision. Over time, it hardened into moral dogma.

When that rule is treated as absolute, it creates a paradox. Gotham is protected in moments and condemned in the long run.

For some readers and players, that tension adds depth. For others, it breaks immersion completely. For me, it answered a lingering question.

Batman did not fail because he is dark. He failed because his fear became law.