There is something slightly disarming about how calm Matt Murdock feels at the beginning of Underboss. He believes he understands the city. He believes he knows who holds power and how that power works. Most of all, he believes that threats reveal themselves when they matter.

Those beliefs were a huge mistake.

In Underboss, Matt Murdock faces a new kind of threat in Hell’s Kitchen. It announces itself through legitimate business, legal maneuvering, and the quiet consolidation of power. By the time he realizes what’s happening, the battle is already lost. Daredevil is outmaneuvered by a system that has already decided where he fits.

And… it’s not at the table where decisions are made.

Reading reference: Daredevil (Vol. 2) #26–31, “Underboss”

The illusion of control at street level

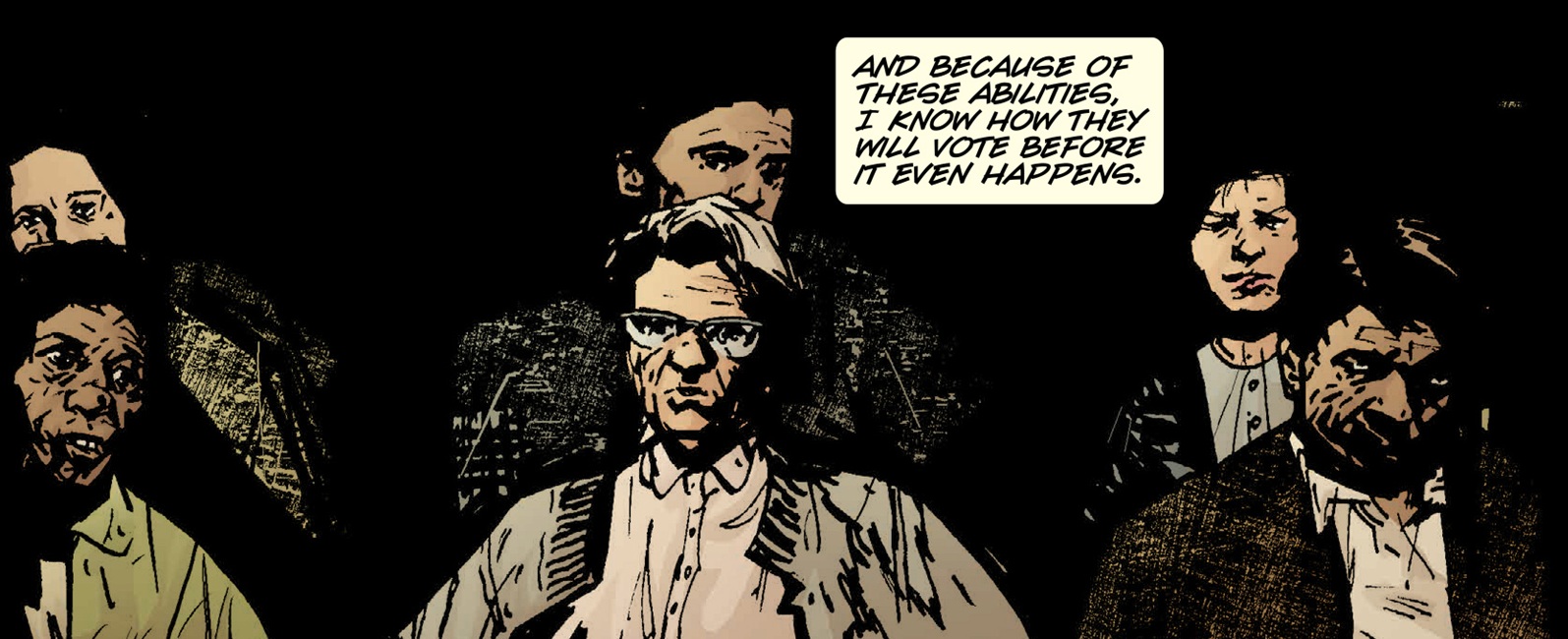

Matt Murdock operates with confidence because his experience has taught him to read immediate danger. He can track a mugging three blocks away by the sound of a scuffle. He knows the heart rhythms of crime bosses, understands the language of intimidation, and recognizes fear in someone’s voice when violence is about to erupt.

Underboss exposes how incomplete that skill set is.

What Matt doesn’t notice is the legitimate businessman quietly buying up property in Hell’s Kitchen. The lawyer filing incorporation papers for shell companies. The re-zoning applications that are submitted through proper channels. The restructuring of debt that looks perfectly legal on paper. These aren’t threats in the language Matt has learned to read. They don’t sound like danger.

Street-level awareness creates the illusion of control. Matt believes if something is wrong, he will feel it coming. He assumes that power presents itself through force or fear. This assumption (figuratively) blinds him to the slow rearrangement of power happening around him. Transactions filed in triplicate, approved by the city, stamped with official seals.

The story shows that power doesn’t need to confront you to neutralize you. It only needs to redirect the flow of decisions until your choices no longer matter.

Power consolidates through legitimacy, not fear

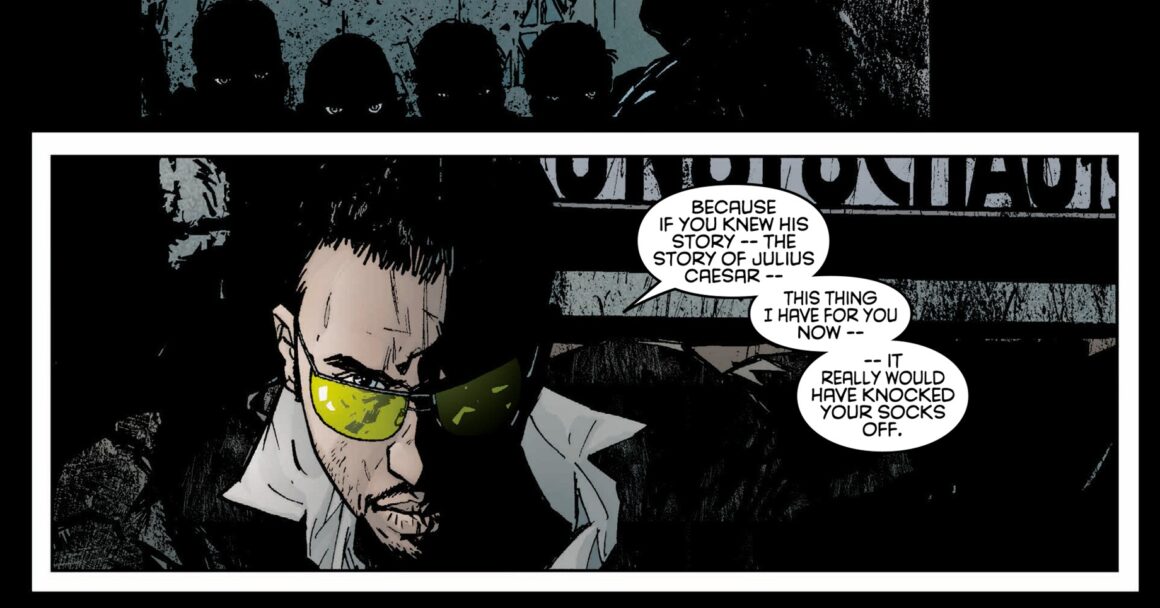

One of the most unsettling things about Underboss is how calm its power structures are. The rising power in Hell’s Kitchen is people in suits holding meetings and signing contracts. Nobody is rushing or panicking. The people benefiting from the shift in power understand that legitimacy protects them better than intimidation ever could.

Crime becomes administrative. Influence becomes procedural. Violence becomes a last resort rather than a language. The new power doesn’t need to threaten Daredevil directly. It operates in spaces where his abilities are irrelevant. You can’t punch a zoning board. You can’t intimidate a legal filing.

Matt struggles here because legitimacy is harder to fight than cruelty. A thug in an alley can be stopped. A properly executed business transaction, backed by lawyers and filed through official channels, is a different kind of opponent entirely.

This is where Underboss quietly reframes the battlefield. Daredevil is used to opposing criminals. People who operate outside the law who can be caught, exposed, and stopped. He’s unprepared to oppose stability that masks corruption, or systems that believe they’re operating correctly even though they cause harm.

The irony? He’s a lawyer.

Naivety as moral confidence

Matt’s naivety in Underboss is based on moral confidence. He believes being right matters. He believes good intentions carry weight. He believes exposure leads to accountability. If he can show people what’s really happening, the system will correct itself. These beliefs have sustained him emotionally through years of fighting in Hell’s Kitchen. But… they leave him strategically vulnerable.

Underboss shows how easily moral confidence can be exploited. When others recognize your principles, they can predict your responses. They know what Matt Murdock will and won’t do. They know he’ll work within certain boundaries, trust certain institutions, and appeal to certain authorities. They can move around him instead of through him.

Matt keeps expecting resistance to look like opposition. Someone pushing back, fighting him, trying to stop him. Instead, it looks safe. Doors open when he knocks. People are polite. His concerns are noted. Nothing changes.

When violence is no longer the threat

Perhaps the most important power shift in Underboss: Daredevil isn’t being hunted. He is being made irrelevant.

The consolidating power in Hell’s Kitchen doesn’t need Matt Murdock gone. It needs him contained in “the good old days” mentality. Assumptions that crime looks like back-alley deals. Power reveals itself through intimidation. The law is a tool for justice rather than leverage. While Matt patrols the streets and waits for conflict, power reorganizes itself so completely that confrontation becomes unnecessary.

He’s still out there, fighting yesterday’s battles while today’s war is being won in conference rooms and city offices.

This is where the story becomes unsettling in a very grounded way. The danger is normalization. Once a new order feels stable, has the appearance of legitimacy, the backing of institutions with paperwork in order, opposing it looks disruptive.

Disruptive people can be managed.

Endurance begins before the reveal

Underboss was my first Daredevil comic. It works so well as an entry point because it sets the emotional trajectory for everything that follows. The arc establishes a pattern: Matt trusts structures (the law, the system, the idea that truth matters) that were never designed to protect someone like him.

Later in Bendis’ run, when Matt’s secret identity is exposed to the public and his life unravels, his shock and devastation make perfect sense. The groundwork was laid here, in Underboss, when he placed his faith in systems that seemed stable and legitimate, only to find out they were littered with loopholes.

The story asks the reader to recognize an uncomfortable truth: Power rarely needs to announce itself to win. It only needs time, legitimacy, and someone willing to assume it will behave responsibly.

Matt Murdock assumes that. Underboss shows why that assumption is dangerous.