I finally sat down and read the 1982 graphic novel X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills and wow. I don’t even know where to start because it starts rough.

Two kids are gunned down by the Purifiers, an anti-mutant terrorist organization determined to eradicate all mutants. Their bodies are strung up in a playground with a slur placed on them. Two innocent children died because they were mutants.

How religion turns hate into salvation

Chris Claremont wrote this comic in 1982, during the rise of televangelism and the Moral Majority. It was a period obsessed with purity and “restoring Christian values.”

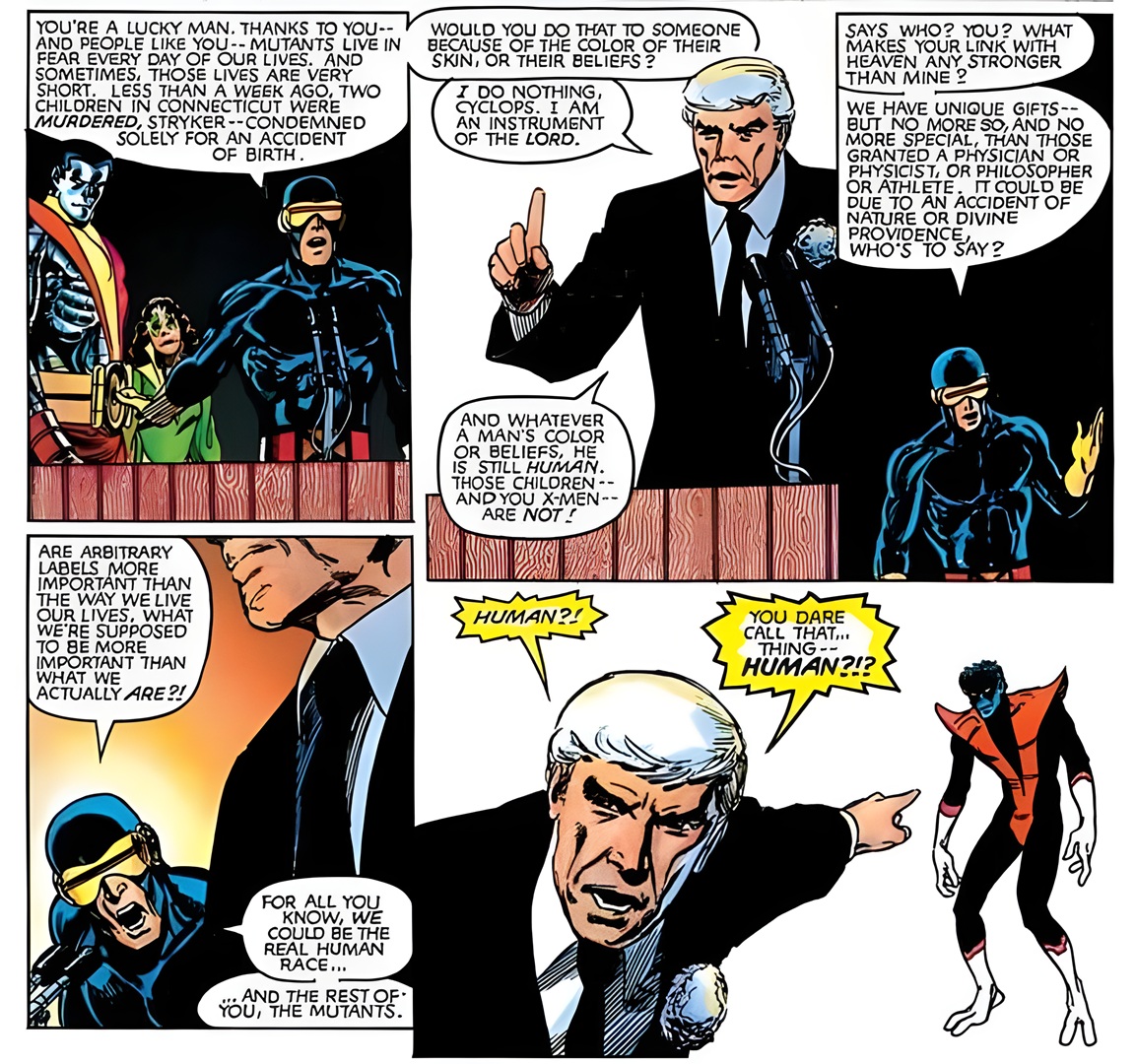

Reverend William Stryker is a symbol of how religion can be turned into a weapon against marginalized groups of people. He doesn’t have any superpowers, yet he’s able to spread his message of hate to millions of Americans.

Presenting himself as charismatic and personable, Stryker would include Bible verses in his sermons that complimented his anti-mutant rhetoric. His words resonated with those who were fearful of mutants due to them being a growing population of superhumans who could potentially replace normal humans.

Stryker validates their concerns by painting mutants as the creation of Satan who must be destroyed. Chris Claremont doesn’t sugarcoat how extremism spreads. For some people, it doesn’t take much to go from “I’m scared of mutants” to “let’s kill them on TV and call it salvation”?

That’s what makes William Stryker so disturbing. He’s got a media empire to spread his agenda throughout the country. He’s the leader of the Purifiers who are devoted to his mission. He takes a fear that already exists and gives it direction.

Televangelism hides Stryker’s cruelty

Stryker weaponizes a particular kind of intimacy. On television screens, he smiles into the camera while calling for genocide. The medium softens him. Viewers feel like they know him. That’s what makes televangelism so dangerous. It makes ideology personal. You don’t just believe Stryker, you trust him.

Claremont knew exactly what he was doing. The 1980s were full of pastors who built empires out of fear. Stryker is their exaggerated reflection.

The worst part is that Stryker’s crusade works because his audience supports him. They don’t commit violence themselves, but they create the environment where it’s accepted. They’re complicit by giving Stryker a platform in the first place.

Moral clarity without comfort

The story doesn’t give you a clean ending where everything is fixed. At best, the X-Men stop Stryker’s plan to use Professor Xavier to kill all mutants.

And that’s it. There’s no ending where everyone learns to accept mutants. The X-Men are aware of how LIMITED their influence is. They can’t just throw Stryker in jail and call it a day. He has millions of followers, some of them being fellow evangelists or politicians. You can’t defeat an idea the same way you can take down a supervillain.

Speaking of villains, Magneto teams up with the X-Men to stop Stryker because the threat is THAT bad. It doesn’t resolve their differences, but it does mark the start of Magneto’s transition into a more heroic character.

The whole comic is an honest, realistic portrayal of how saving the day can only get you so far.

Being Heroes Doesn’t Offer Any Protection

One thing that really stuck with me is that being SUPERHEROES doesn’t protect the X-Men. They’re not universally adored by the general public. Instead, the team are scapegoats for humans to project all their fear and intolerance onto.

Once a mutant is publicly identified, they have a target placed on their backs. It doesn’t matter what type of personality they have, whether their powers are destructive or can be used for good. The fact that mutants exist is unnerving for some people.

The X-Men challenge the idea that representation alone is enough. Sometimes being seen just makes you an easy target. Nobody wants to talk about the costs of demanding visibility. What happens when the people watching don’t have your best interests in mind?

Why God Loves, Man Kills Resonates Today

What makes God Loves, Man Kills a classic is that it shows how fear is harnessed by people who claim hurting innocents is the RIGHT thing to do.

The story doesn’t ask “is hatred wrong?” We know it is. It asks “why is it allowed to spread?”

And that question extends BEYOND mutants, doesn’t it? The comic can be rewritten to be about immigrants, Jews, Muslims, the LGBTQ+ community and it will still get its point across.

The rhetoric is familiar. It pops up in media coverage of immigration enforcement, in debates about gender-affirming care for trans people. The outcomes are devastating for the ones affected by it. And every step of the way, people justify it.

Stryker’s crusade isn’t a relic. It’s a blueprint that is reused over and over again because it keeps working.

Once you see that pattern, you see it everywhere.