Amazon Prime Video’s take on Garth Ennis’ The Boys isn’t trying to be a faithful adaptation of the comic. Ennis hated superheros as he didn’t believe people with the abilities of Superman would actually use those gifts for good. The Boys was a scathing deconstruction of the concept, exploring the corruption and destruction heroes leave in their wake.

Showrunner Eric Kripke scales down the more horrific aspects of the comic. Instead, he gives us a more nuanced look into the damage the Supes inflict on the world around them. We see characters struggle with keeping their humanity as the trauma continues to pile up. The show also does a better job at depicting how Starlight handles her first day at Vought.

Starlight’s First Day at Vought

Starlight (Annie January) is the small-town girl who joins the Seven thinking she’s going to help save the world. In the comics, Ennis destroys her on day one. The TV show gives her some more depth.

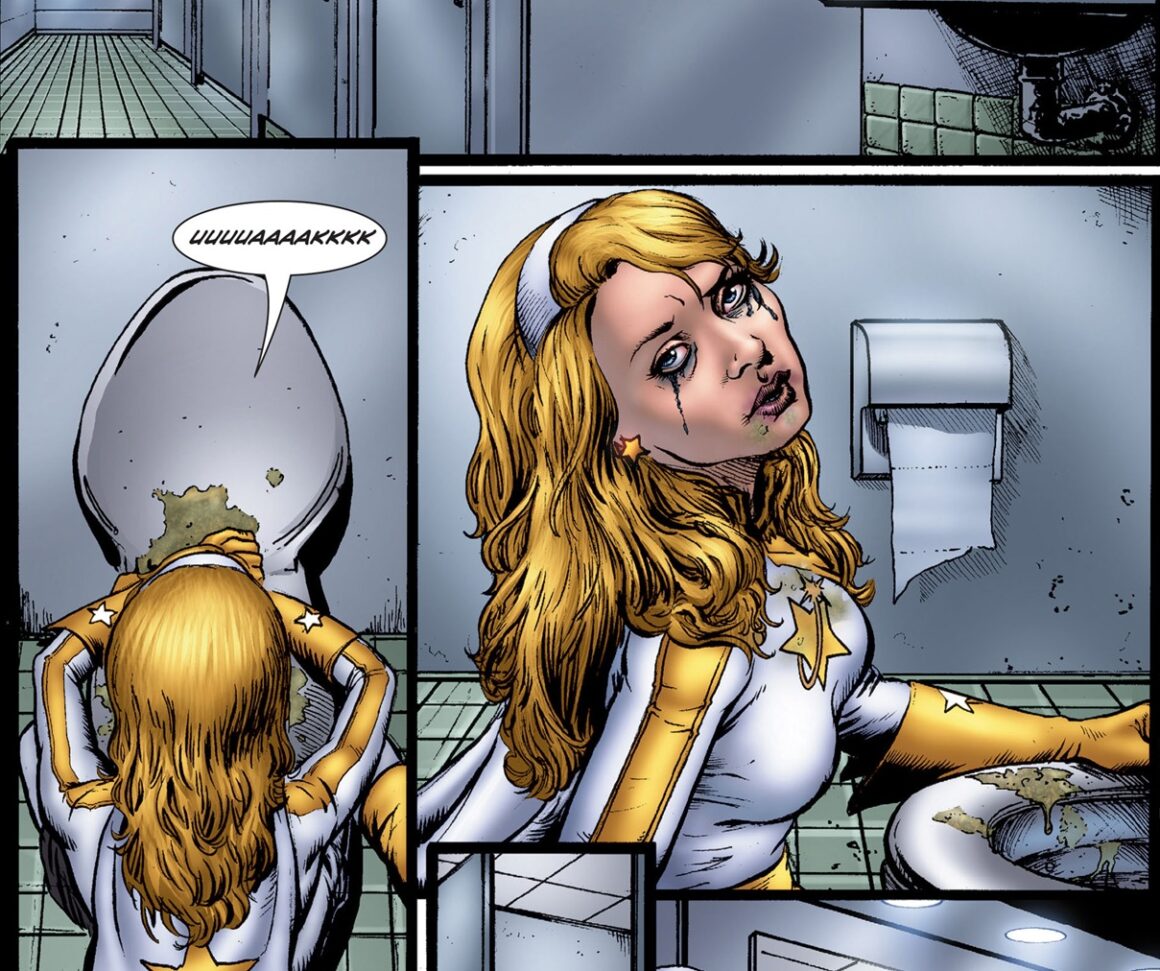

In the comics, Starlight is coerced into giving Homelander, Black Noir and A-Train oral sex. It’s abrupt with no real build-up behind it. The act is pure shock value meant to demonstrate how morally bankrupt The Seven really is.

For the first episode of season 1, “The Name of the Game,” the moment is presented very differently.

The Deep is the sole instigator. He doesn’t drop his pants until he’s alone with Starlight and she mentioned having a crush on him when she was younger. He lies about being second-in-command, while insisting it’s what she needs to do to stay on the team. When that doesn’t work, The Deep threatens to tell Homelander Starlight attacked him if she doesn’t comply. In The Boys universe, that threat is the equivalent of threatening to push someone in front of an oncoming train.

The scene is more grounded that sets up Starlight’s arc for the season, while retaining Ennis’ point about corrupt people using their status to exploit others.

The Problem With Maximum Trauma

The issue I have with Ennis’s approach is he mistook maximum trauma for maximum impact.

By making Starlight’s first-day so utterly devastating , he actually reduces the story’s power. There’s nowhere for her character to go except Stockholm Syndrome or resilience. She either breaks completely or she doesn’t break at all. Neither option feels like watching a real person navigate an impossible situation.

It’s shock value with diminishing returns.

The showrunners for the show understood something Ennis didn’t. Sometimes with horror, a “less is more” approach is more effective. The Deep’s harassment of Starlight is something that (unfortunately) can happen in the workforce. It’s dark and unsettling without going overboard.

Starlight’s gradual disillusionment in the Amazon adaptation is more painful to watch than immediate destruction because we see her trying. She makes small compromises that lead to bigger ones, and we see the moment she decides enough is enough.

Why Choices Matter More Than Consequences

When someone is destroyed repeatedly like Starlight is in the comics, we feel pity. Maybe we feel outrage. When someone is put in a position where they have to choose between bad options and worse options? That’s when we start to squirm.

The show gives us a Starlight who joins the Seven with her eyes wide open, yet is oblivious to the corruption underneath. When harassed and threatened by The Deep, instead of leaving immediately, she makes a choice to stay. She still believes being on the team is the best way to help people.

That’s the key difference. Starlight has agency, even if it’s limited agency.

Over the course of the first season, we watch her try to work within the system. She pushes back against The Deep and later A-Train. She stands up in small ways. She tries to be the change from within, which is what so many people do in toxic workplaces, relationships, and corrupt institutions. This is human behavior, not a plot point in some comic book designed to make readers feel uncomfortable.

What Does This Say About Ennis?

Why did Garth Ennis write Starlight’s assault the way he did, thinking the over-the-top humiliation was necessary?

Perhaps he was writing from a place of deep cynicism about post-9/11 America and celebrity worship. He wanted readers to feel complicit. If we keep reading after that scene, we’re like the public that keeps worshipping these monsters despite knowing what they are. It’s also provocative, designed to make you uncomfortable with your own desire to read the rest of the story.

But… it’s also manipulative.

Ennis confused punishing his characters with punishing his readers. He wanted to make us feel bad for enjoying superhero stories, so he made the worst possible thing happen to his most idealistic character as quickly as possible. “Look what you made me do,” the comic seems to say.

Ironically, this is where Ennis’s own cynicism undermines his point. By going to the extreme, he lets readers off the hook. We can say, “Well, that’s not realistic,” and dismiss the whole thing as an exploitation comic. We don’t have to sit with the uncomfortable truth that abuse happens at work or imbalanced power structures.

What the Show Gets Right

The show’s version of Annie January starts in roughly the same place. A genuinely idealistic small-town Christian girl who grew up believing the Seven are true heroes. She sees joining them as both a calling and validation of her faith and moral ideals.

But the journey is different.

Her relationship with Hughie becomes central in a way it couldn’t be in the comics version, because she’s not completely shattered. She’s conflicted. Both of them are new to their respective worlds (the Boys and the Seven). They bond as two overwhelmed, basically decent people trying to process how ugly things really are. Hughie gives her someone normal to confide in, while she gives him a living counterexample to the idea that all supes are irredeemable monsters.

Their relationship only works if both characters have enough of themselves left to actually connect with another human being.

Behind the scenes, Ennis himself apparently figured this out while writing the comics. He’s said that Annie originally started as more of a joke who would sink further and further into degradation. However, writing the park meeting with Hughie made him reorient her into a stronger, more rounded character. She became one of the few genuine heroes in that universe. Someone who keeps her core compassion and helps bring down the Seven rather than being completely destroyed by them.

But he’d already locked himself into that first-day trauma. The pivot feels abrupt in the comics because he had to pivot at the last minute.

How we portray abuse and recovery matters.

The comic’s version suggests that real idealism gets destroyed as soon as you enter the real world. The show’s version shows how idealism is tested, compromised, beaten down. And then it’ll break or evolve into something more resilient and more realistic. One version matches how people react to the corrupt system they find themselves in.

The show lets Starlight be angry without being broken. She makes mistakes without making those mistakes define her. She’s learning that her faith doesn’t have to be in institutions, but in doing the right thing regardless of institutions.Ennis gave us a character who survives in spite of her trauma. The show gave us a character who evolves because of her trauma. There’s a huge difference.