Remember when you first met Stick in the Netflix Daredevil series? That scene where he shows up at the orphanage, all gruff and mysterious, telling young Matt he can “make him strong”? If you’ve read Frank Miller’s comics, you might have thought you knew where this was heading. A blind mystic ninja trains a blind kid to become a superhero. Classic origin story stuff.

Nope! The show took the familiar and turned it into something much darker. Something that would echo through every decision Matt makes for the rest of the series.

The training scenes in both versions? Brutal. The ninja skills? Check. The radar sense development? Present in both. But… somewhere between the page and the screen, Stick transformed from a harsh sensei into something that starts to look uncomfortably like child abuse.

That shift changes everything.

How It All Begins

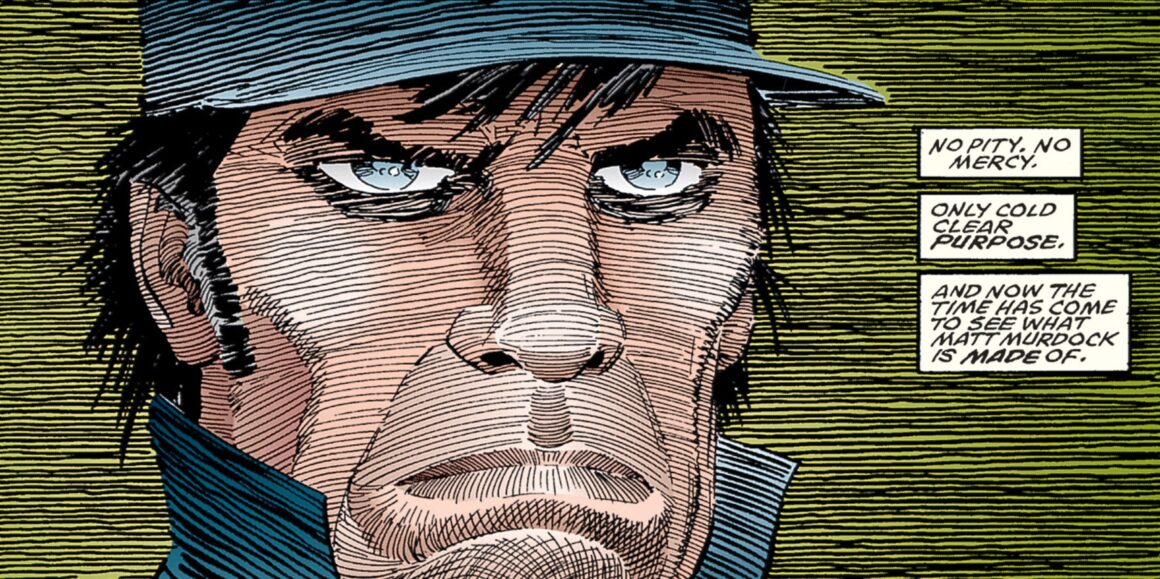

In the comics, particularly Frank Miller’s “The Man Without Fear,” Stick finds Matt pretty quickly after the accident. He recognizes the potential in this blind kid with enhanced senses and decides to train him. Yes, it’s calculated but there’s a sense of purpose.

Stick is shaping a warrior for the Chaste’s war against the Hand. Matt doesn’t fully understand what he’s being prepared for, but the training happens over years, stretching into Matt’s late adolescence. Then Stick leaves. Abruptly. No explanation that really satisfies.

The TV show takes a different approach. Stick doesn’t show up until Matt is already grieving at St. Agnes orphanage after his father’s murder. The timing matters here. Matt isn’t just a kid who had an accident. He’s a traumatized child who just lost his only parent. And into that vulnerability walks Stick with his offer to “make him strong.”

That’s exploitation of a kid at his lowest point.

The show reveals all this through flashbacks in season 1, and those scenes hit differently when you realize Stick is targeting a grieving child. In the comics, there’s at least some distance between the trauma of losing his father and Stick’s arrival. The show collapses that timeline. Stick is predatory.

What the Training Actually Looks Like

In the comics, Stick is preparing a warrior. The training is harsh because the stakes are high. There’s a mystical war happening between the Chaste and the Hand. Matt needs to be ready. Stick pushes Matt to master his enhanced senses, to detach from fear and grief, to become something more than just a blind kid with abilities. It’s spiritual-martial training with a clear (if hidden) purpose.

The show has a different story: pain and physical abuse disguised as boot camp.

You’ve probably seen the training montages. They’re hard to forget. Young Matt, maybe nine or ten years old, getting hit with sticks while Stick barks orders. Matt’s hands are bleeding from hitting a brick wall over and over. Stick stands there, watching this child hurt himself. When Matt flinches or cries out, Stick mocks him for weakness. “You think the world is a nice place?” he sneers. “It’s not. I’m teaching you to survive it.”

Conditioning through pain.

The mystical war context is there in the show. Black Sky, Nobu, all of that comes later. It’s revealed slowly, almost reluctantly. For most of season 1, we see an old man hitting a child and calling it training.

Ironically, this shift makes the show’s version more realistic in a disturbing way. Because this is what abuse looks like. It’s always justified as “for your own good” or “making you stronger.” The abuser always has a reason.

The Abusive Father Figure Arc

Let’s talk about Stick’s personality, because this is where the show really diverges.

Comics Stick is harsh. Ascetic. Often cruel. But… he’s operating from a specific philosophical framework: detachment from emotion, mastery of self, preparation for war. When Matt becomes too emotionally attached (there’s a moment with a bracelet in both versions), Stick leaves. It’s brutal, but it’s consistent with his worldview. Attachment is weakness. Matt got attached. Stick left.

TV Stick? That harshness gets turned up and mixed with something much more sinister. He doesn’t just push Matt away when emotions surface. He mocks them. He judges adult Matt’s no-killing rule. He criticizes Matt’s attachments to people. He keeps coming back into Matt’s life specifically to tell him he’s doing it wrong.

This creates what the show clearly intended: a central “abusive father figure” arc that runs through the entire series.

The Evidence Stick Actually Cared

The plot twist: Stick does care. He keeps coming back. He warns Matt about the Hand in season 1. He returns in season 2 to help protect him.

If Stick truly didn’t care, why didn’t he stay away? The Chaste has its own mission. Matt isn’t Stick’s responsibility anymore.

Scott Glenn, who played Stick in the show, mentioned in interviews that Stick kept saying Elektra had to die but kept saving her life. There’s this pattern of Stick being unable to follow through on his own harsh philosophy when it comes to people he’s raised.

He cared about Matt. He cared about Elektra. But… his way of caring is so emotionally stunted, so wrapped in his brutal worldview, that it comes out as cruelty disguised as preparation.

That’s the tragedy. Love exists, but it’s expressed through abuse. Care exists, but it’s channeled through abandonment and judgment.

Stick genuinely believes that attachment is weakness and that the best thing he can do for Matt is keep him at arm’s length while occasionally showing up to criticize his life choices.

It’s a heartbreaking father figure dynamic. The show mines it for everything it’s worth.

The Elektra Manipulation

Remember how Matt and Elektra met in the comics? She’s this intriguing woman who shows up at college. There’s mystery, attraction, a romance that develops. Later, much later, we find out about her training in Japan, her connection to the Chaste, her history with Stick. The manipulation is there, but it’s revealed as a twist, not the foundation.

The show flips this entirely.

Stick personally raises Elektra from childhood. Trains her. Shapes her. Then, and this is crucial, he deliberately sends her to Matt as part of a mission to recruit him into the war against the Hand.

Picture the ice cream wrapper bracelet moment again. Young Matt, offering Stick this handmade gift, thinking maybe this is what family feels like. Stick leaves because Matt got attached. Matt learns: attachment equals abandonment.

Now fast forward. Matt meets Elektra at college. Falls for her. Finally lets himself feel something. It turns out she was sent by Stick. The romantic relationship that made Matt feel like maybe he could have love after all? Orchestrated by the man who taught him love was weakness.

Think about what that does to Matt’s understanding of relationships. The woman he loves was sent to him by his abusive father figure as part of a recruitment strategy. Even his romantic relationships aren’t safe from Stick’s interference. Even his feelings aren’t entirely his own.

In the comics, Elektra and Matt meeting feels organic (even if it’s later revealed to be influenced by larger forces). In the show, their romance is a side-effect of Stick’s manipulation from day one.

That’s devastating. It recontextualizes everything about their relationship and adds another layer to Matt’s trauma. He can’t even trust that his deepest emotions are real or manufactured.

Why This Matters for Matt’s Character

Here’s where the show’s choices really pay off narratively, even if they’re darker than the comics.

In the comics, Stick’s training explains Matt’s abilities. That’s its primary function. Sure, Stick appears later as a wartime general figure when the Hand shows up, but he’s not a constant presence in Matt’s emotional landscape. The training happened, Matt got skills, Stick left, story continues.

The show makes Stick’s training and abandonment the core emotional engine for Matt’s entire character arc.

- Matt’s guilt? Rooted in Stick’s teaching that attachment is weakness.

- His Catholic conflict about violence? Constantly framed against Stick’s philosophy that killing is necessary.

- His inability to maintain healthy relationships? Direct result of being abandoned by his mentor the moment he showed emotional attachment.

- His no-killing rule that everyone challenges? A rebellion against Stick’s worldview as much as a moral stance.

You can trace almost every one of Matt’s self-destructive patterns back to that orphanage training room.

The show brings Stick back for confrontations in both Daredevil and The Defenders specifically to keep poking at these wounds. Every time Matt thinks he’s moved past it, here comes Stick to remind him of all his failures, all his weaknesses, all the ways he’s disappointed his mentor.

Stick was traumatized by the war with the Hand. He traumatized Matt while training him. Matt now struggles not to pass that trauma forward to the people in his life.

It’s psychologically brutal, and it makes Matt a much more damaged character than his comics counterpart.

The show didn’t just give us a harsher version of Stick. It gave us a version that echoes the complicated, painful reality of how damage gets passed down. How the people who make us strong can also be the reason we struggle. How love and harm can exist in the same relationship, taught by the same hands.

That’s the difference between the versions. It’s why the show’s Stick haunts Matt, and us, in ways the comics’ Stick never could.