In The Boys, the comic book version of Black Noir was Homelander’s secret clone/replacement. The TV version was Earving, a brain-damaged assassin who spent decades doing Vought’s dirty work.

Both Noirs are a look into how corporations view their employees to be interchangeable.

Who Is Black Noir in the Comics?

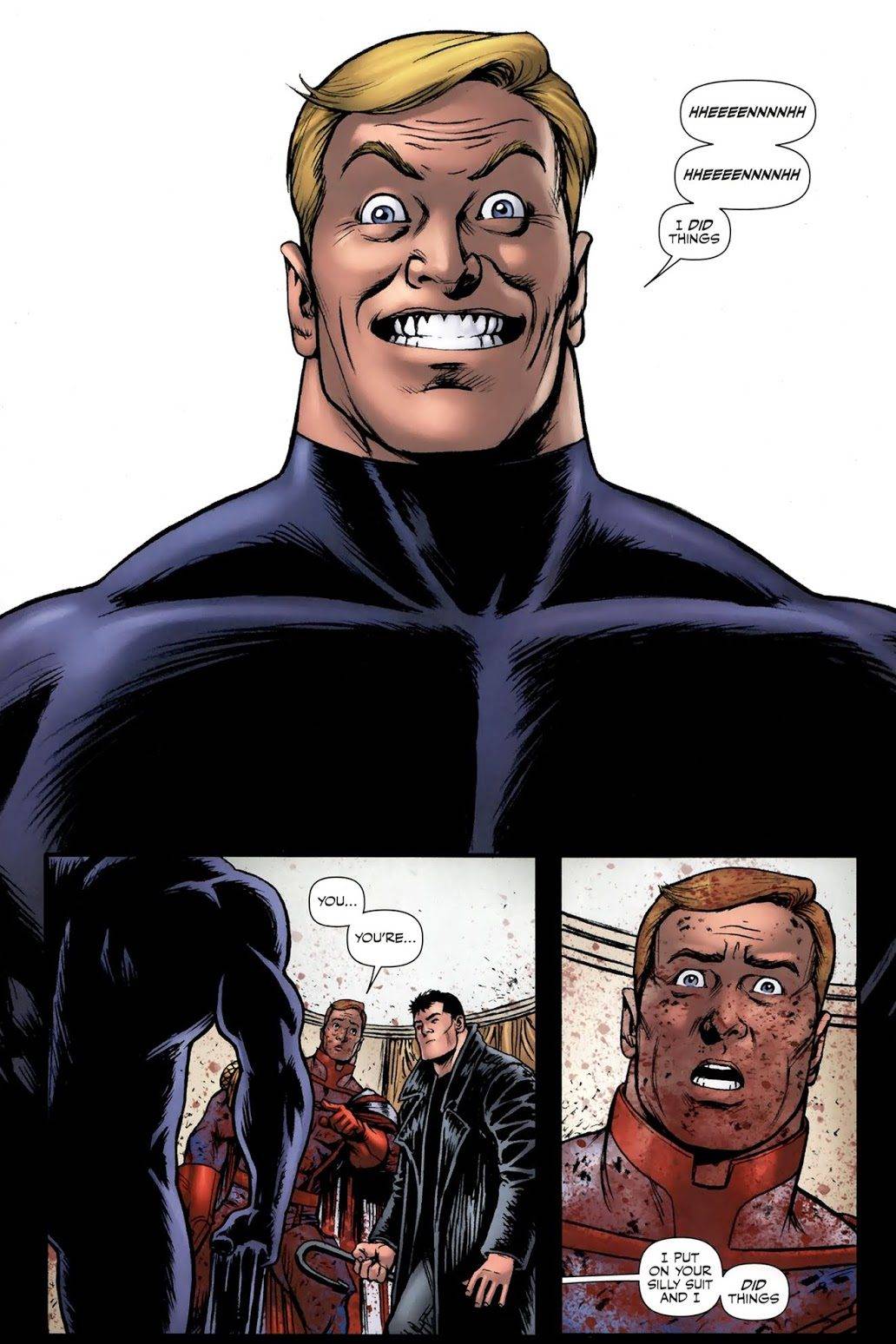

In Garth Ennis and Darick Robertson’s comics, Black Noir was created by Vought as a duplicate of Homelander. He’s nothing more than a failsafe meant to kill their flagship hero if he ever goes rogue.

The problem is that Homelander has been behaving himself for years. Noir never gets the order to strike. Without a mission, he has no identity, no purpose. He’s a spare part sitting on a shelf, waiting for a disaster that never comes.

So he manufactures one.

Noir starts impersonating Homelander, committing atrocities and framing him. He breaks Homelander’s mind on purpose, until he decides to confront the Supe and kills him without waiting on an official order from Vought.

Black Noir in the TV Series

Showrunner Eric Kripke scrapped the clone twist as he didn’t feel it meshed with the TV show’s more grounded setting.

Instead the show gave us Earving, the original Black Noir who’s a separate person. He’s Black supe who wanted to be the next Eddie Murphy. But was forced into a mask because Vought decided that a prominent Black hero was bad for business in the 1980s.

Unfortunately, Earving caught the ire of his teammate Soldier Boy, who destroyed his face and brain during a mission in Nicaragua in 1984. That beating left him mute, brain-damaged, and hallucinating cartoon animals.

Despite the damage Vought brought into his life, he keeps working for them as a member of The Seven for decades. And what does he get for his loyalty? Homelander kills him in Season 3 for hiding the truth about Soldier Boy being his dad.

Hiding Behind the Mask

Both versions use masks, but for different reasons.

In the comics, the mask hides the fact Noir is a clone because he looks identical to Homelander underneath. The mask preserves the twist while adding some mystique to his character.

In the show, the mask erases Earving’s identity, his race, his ambitions and eventually his trauma. Vought buries all of it under a brand that outlives him.

When he dies, they don’t even retire the name. They just hire another Supe to take his place.

This mirrors how corporations treat roles versus people. The job title is visible. The individual doing the work is interchangeable and invisible.

The Brand Outlives the Person

It doesn’t take long for Vought to find a replacement. Season 4 introduces Black Noir II, an actor who’s not very good at his job. He breaks character, he’s not as skilled a fighter like Earving was. He talks constantly and asks questions about how he should act because no one will tell him who the original Black Noir actually was. Black Noir II even has narcolepsy. He falls asleep at the worst moments.

Vought doesn’t care. In fact, they might even view Black Noir II as an upgrade since he can fly, which the original couldn’t do. All that matters is that the public is kept in the dark about Earving’s death.

This is the harsh reality of the corporate world. You can be loyal, competent, even essential. And sometimes, it isn’t enough to save your job. When you’re gone, they’ll place someone else into your role and expect everyone to pretend nothing changed.

To twist the knife even further, the same actor who played Earving Nathan Mitchell portrays Black Noir II. In-universe, the public believes they’re the same person. Behind the scenes, Mitchell gets to play two completely different characters under the same costume.

The move is a meta joke for how Hollywood will cast different actors to play the same “role” of a legacy character like Batman or Spider-Man. It also acknowledges that even the cast and characters of The Boys are technically replaceable themselves.

What Black Noir Represents in The Boys

The comic version of Black Noir is a satire of corporate redundancy. Even your most valuable asset has a backup. Replacing an employee is a form of control for Vought. It’s a message that you’re never as important as you think.

The TV version of Nori tackles the exploitation employees can experience. Vought markets Earving as a mysterious hero while suppressing everything that makes him human. When he stops being useful, they discard him.

Both versions arrive at the same conclusion from different angles: corporations don’t value people. They value functions.

Neither gets to be valued as an individual.